When people find out where I work, their reaction is usually the same. First, it doesn’t completely register. “Oh, interesting.” And then the follow-up question: “What do you do there?” After I tell them that I x-ray human remains, it takes another second for that to sink in. “Oh. OHH!”

I’ll admit that this reaction is a little unusual to me, but that’s because I’ve spent so long researching this line of work that the connection just seems obvious. You work in the morgue, therefore you work with the dead. At least in some capacity.

What usually follows the “ah-ha” moment is one of the following statements:

- “But you’re so small”

- “But you’re so nice”

- “But you’re so quiet.” (My personal favorite.)

I can see why people would think my size influences my ability to work with the dead, but my sound level? I don’t quite understand that one.

Even after all of that, a lot of people still don’t really understand what it is I actually do in the morgue. In this post, I’ll walk you through a typical day.

Elevator pitch: Got dead people? Then you need x-rays! Shave minutes off of autopsies with your very own set of radiographs! Locate bullets faster. Age fractures more accurately. Is that a nickel in the right lung?! No problem!

Heh.

More accurately, I assist pathologists pre-autopsy by providing images of pathologies and traumas. X-rays offer a helpful roadmap in cases where foreign objects or bullets are involved. They also help determine the age of injuries: is this a new fracture or an old one? If new, did it contribute to the person’s death? Additionally, x-rays provide valuable legal documentation, which is important in homicide and abuse cases.

I’ve mentioned previously that we have certain protocols to follow when it comes to determining which bodies warrant x-rays. The first thing I do is read through all the investigation reports to learn the initial details surrounding an individual’s death. As I’ve said, every suspected homicide gets x-rays. This includes gunshot wounds and stabbings. Other cases needing x-rays include falls, motor vehicle accidents, drownings, fires, unknown bodies, and decomposing bodies.

We work in teams of two and each one has a specific role. One person is the “driver” and the other is the “runner”. As the driver, you operate the equipment and make sure everything is loading properly in the computer. You’re also responsible for annotating all of the images and keeping track of the number of x-rays taken and any bullets or foreign objects found.

As the runner, you’re responsible for tagging all of the bodies in the body cooler. This lets the pathologists and their techs know which individuals are going to x-ray. It also makes it easier for you to find the next case. Gunshot wounds take priority and get a red card, while everything else gets a yellow card.

I find this process unsettling at times. Usually it’s just you alone in the body cooler. At any given time, I’d estimate that there are close to 200 bodies in there. Many of them are being stored or awaiting transport to a funeral home. Only about 20-30 are actual cases for the day. You’re literally surrounded by death. It’s a heavy realization so early in the morning.

A co-worker likes to use this time to introduce herself to our cases. I’ve, on occasion, will say good morning to the cooler’s occupants. Sometimes talking while in there calms my nerves. Other times it makes me irrationally worried that I might hear a “good morning” in return.

The runner also transports the bodies to and from the x-ray room and positions the body for imaging. Obviously the runner is much more hands on with the bodies. This doesn’t usually bother me, but some cases are more difficult to stomach than others. More on that later.

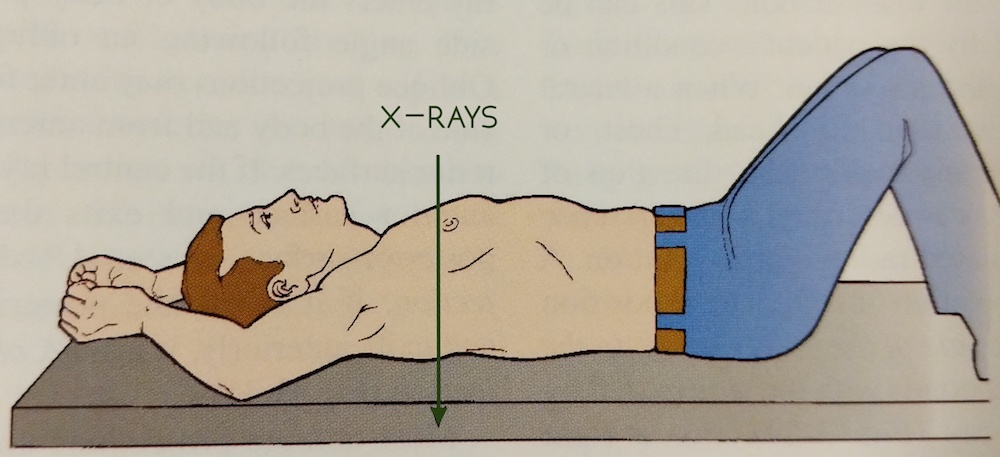

By default, every individual requiring x-ray will get at least one skull and one chest image. Most cases will get the standard protocol: skull, chest, abdomen, pelvis. Any area of trauma will also be imaged. In the event that the person is unknown, in addition to the standard protocol, we will take an x-ray of every long bone in the body: hands, forearms, arms, thighs, legs, and feet. All of these are performed with the body lying supine (on the back). These are called AP views.

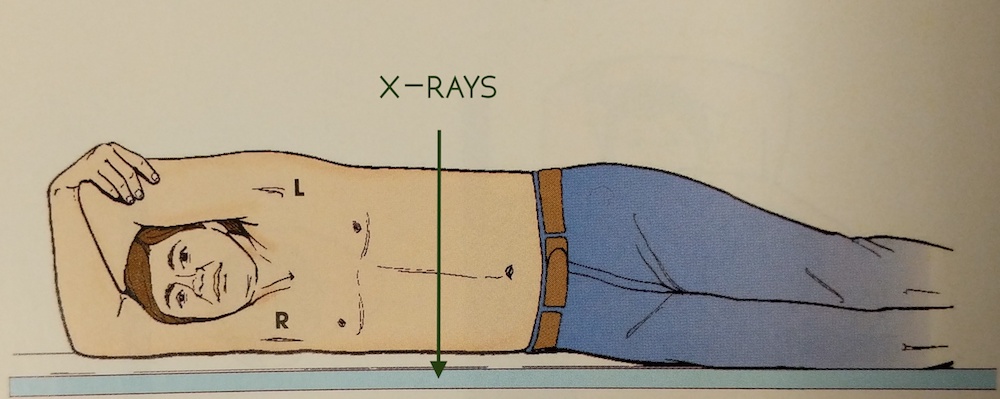

When there are bullets involved, we look for entrance and exit wounds. We cross our fingers for exit wounds because that means the bullet is no longer inside the body. This is good because we don’t have to do additional x-rays, and the pathologist doesn’t have to remove a bullet. But when there is no exit wound, we have to turn the body and get lateral views, meaning that the x-rays enter the right side of the body and exit the left side. This is different from the AP views, which enter the anterior (front side) and exit the posterior (back side).

When you’re the runner, positioning for the lateral views falls on you. Most of the time it will require both technologists because many of the bodies are large. Let’s say someone was shot in the chest and they’re still holding a bullet. A lateral view will help a pathologist determine if the bullet is closer to the anterior or posterior surface. In order to get an unobstructed lateral view of the chest, the arms must be pulled above the head.

Did you read my post about decomposing bodies? If you did, then you know that most bodies on my x-ray table are in the rigor mortis stage of decomposition. This means that their muscles are severely contracted and moving extremities is very difficult. Nevertheless, it must be done. This is my least favorite part of the job. Not only do I feel like I’m always losing a very strange arm wrestling contest, but as the arm is pulled, there are cracks and pops. Occasionally you’ll dislocate a shoulder (theirs, not yours). And in cases where there is a lot of trauma to the arm, pulling it over the head can worsen the damage.

When the arms are successfully over head, they don’t always stay there. When you break rigor mortis, the muscles become more pliable. So when you put a body part somewhere, say an arm, it doesn’t always stay. Smart techs will use rope and sandbags to hold them in place. I? I am not a smart tech.

During a recent case, we had just taken a lateral chest x-ray. I was holding the body up on its side until the x-ray appeared on screen. You don’t want to move a body out of the lateral position until you’re sure you got the image. “All clear.” So I began to roll the body onto its back. As I did, the right arm began to leave its overhead position and swung down to slap me in the face.

F-word.

This is not unusual. In fact, it’s somewhat of an initiation for x-ray techs in the morgue. I hear the other is to have a body fall off the cart. I pray to the powers that be that it never ever happens to me.

Ever.

What made the slap worse was that it happened on the day I decided to take my mask off because every time I breathed it made my glasses foggy. Sigh.

Laterals are usually saved for last because of the likely chance that you’ll get a hand to the face. Or boob. Or ass. Death has no boundaries.

When we’re finishing up our x-rays, the pathologists are just starting their autopsies. We return to the radiology office and hang out until the autopsies are done, just in case a pathologist requests additional views or asks for help locating a bullet. When that happens, the pathologist will bring a body back to the x-ray room. I hate this because the body has already been dissected. Their chest and abdominal cavities are open, void of all their organs. Often times the skin around the skull has been pulled back and the brain is missing too.

It’s an odd feeling. Hours ago, there was a complete person on my table. Aside from whatever trauma they came in with, they were intact. They were whole. Now the shell is broken. The weight of the job is something I still struggle with. The separation of the person from the body doesn’t always happen instantaneously. Instinctually, I feel bad because the body is missing the parts that made it go: the heart and the brain. But I have a job to do so I must quickly flip the switch, disconnect, and see just a vessel. Not a person.

When all is done, we clean up the room. Any blood that reaches the floor stays there until the janitor comes through after our shift, but we wipe down the machines and our table so it’s ready for tomorrow’s guests. We return to our office, sometimes in silence, but usually in conversation, trying to shed the emotional weight. It’s weird. Some days are easier than others. In the beginning, it was difficult not to bring any my work home with me (not in the literal sense). I’d close my eyes while in bed and see the faces of the day’s cases. It was very unsettling.

Talking about it helps. Writing and working through my feelings is cathartic. I’m getting better at creating and enforcing emotional boundaries. Viewing it as a learning experience also helps. I don’t know how long I will be able to work at the morgue. It’ll be a constant challenge and will require a continuous balance of empathy and distancing. For now, it’s just too damn interesting to quit. So we’ll see what happens.