Fun fact! We once thought that infusing water with radium was a great idea.

Okay, so my idea of a fun fact probably differs from that of most, but here we are, discussing radium water. I recently found my audience engrossed as I talked about all of the stupid ways we used radium in the past. One of the most interesting stupid inventions is Radithor.

You’ve never heard of Radithor? Well, sit down because I’m going to fill your brain with so much information about it—more than you ever cared to know, I’m sure. Let’s start with the basics.

What is radium?

Radium is a radioactive element that was discovered by Marie Curie in 1898. Fun fact about Marie Curie: She was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, and the only woman to win two Nobel Prizes.

Radium releases radiant energy with every nuclear decay. This means that as time passes, the nucleus of the atom breaks down and releases energy that does bad stuff. You should know that it’s taking all of my strength not to dive into the physics behind radioactivity and half-lives. You’re missing out, but you’re welcome.

Long story short-ish, if something is radioactive, it’s not good. Radiation causes ionization of atoms, which results in unwanted chemical reactions in cells. At its worst, it can damage DNA, prompting an increased risk of cancer, genetic mutations, and even death.

What’s the Likelihood I’ll turn into the Hulk?

At this point you might be thinking, “But Jenn, don’t you work with radiation every day?” Why yes, blog reader, I do. But there are different types of radiation. For example, alpha and beta particles do a lot of harm, while x-rays and gamma rays cause little harm, relatively speaking. So there’s a small chance of me Hulking out any time soon.

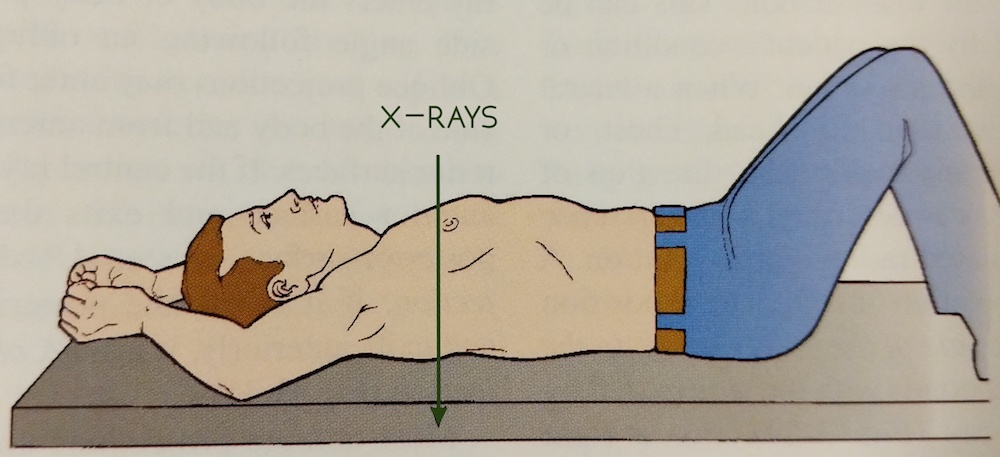

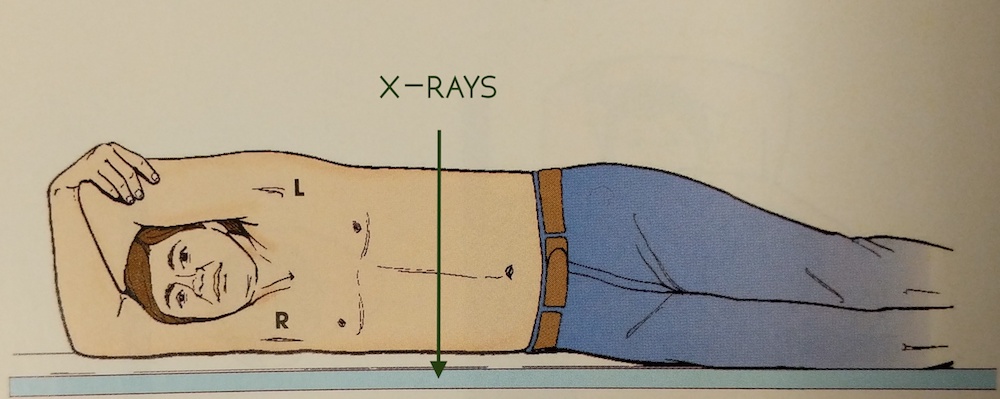

That said, it would be irresponsible of me to withhold this: there is no such thing as a safe dose. There’s always a risk when it comes to ionizing radiation. That said, don’t run out screaming the next time your doctor orders an x-ray. Imaging tests are ordered by doctors after weighing the benefits against the risks. X-rays are taken (and should be taken) by licensed professionals trained to limit exposure while maintaining the integrity of a diagnostic image.

Radithor! And a lot of science

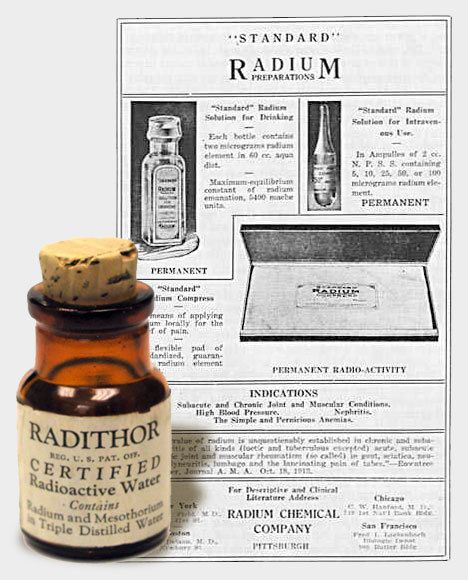

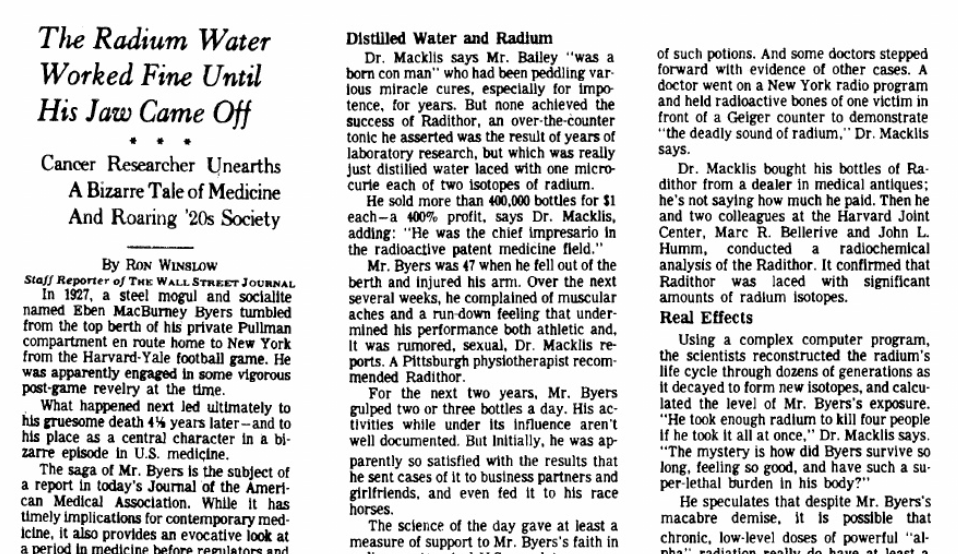

Radithor was invented in 1925 by a man named William Bailey. His triple-distilled water enriched with radium salts was advertised as “perpetual sunshine”. Bailey claimed it could cure over 150 diseases. Spoiler: It couldn’t. Each tiny, half-ounce bottle contained one microcurie each of radium-226 and radium-228. The key takeaway here is that Radithor was legitimately poisonous.

Bear with me or skip to the next section. Radium-226 is a product of uranium decay. It has a half-life of 1,600 years (!!!) and emits alpha particles. Radium-228 is a product of thorium decay. It has a half-life of 5.75 years and emits beta particles. Unlike x-rays, which are capable of exiting the body, alpha and beta particles can be stopped by a sheet of paper or aluminum, respectively. This means that they make it about a centimeter into the body and stay there doing very bad things.

What made Radithor so dangerous? Radium-226 and radium-228 decay at a rate of over four million times per second! Each of those four million radiation bursts find something to hit and destroy in the body. That’s a lot of very bad things! What’s worse is that the radiation rate for radium-228 increases by over 10% after a person stops ingesting it. So even after 80 years, a small bottle of Radithor would max out a Geiger counter. I KNOW!

Radithor! And just a little science

Despite its lethality, 400,000 bottles of Radithor were sold over five years. The most notable consumer of this product was Eben Byers. He began drinking Radithor in 1927 after hurting his arm. He quickly upped his intake to three bottles a day after claiming to feel “instantly” better. He believed that it truly helped. Spoiler: It didn’t. He believed it so much that he started sharing Radithor with his friends, girlfriends, and even his horses.

The problem with ingesting radium is that it’s similar to calcium in terms of its orbital outer-shell electron structure. This means that calcium and radium form chemical bonds the same way. Do you see where I’m going with this? When the body finds radium, it will use it, even if what it really needs is calcium. So when Byers’ body demanded material to repair his fractured arm, it found plenty of radium available.

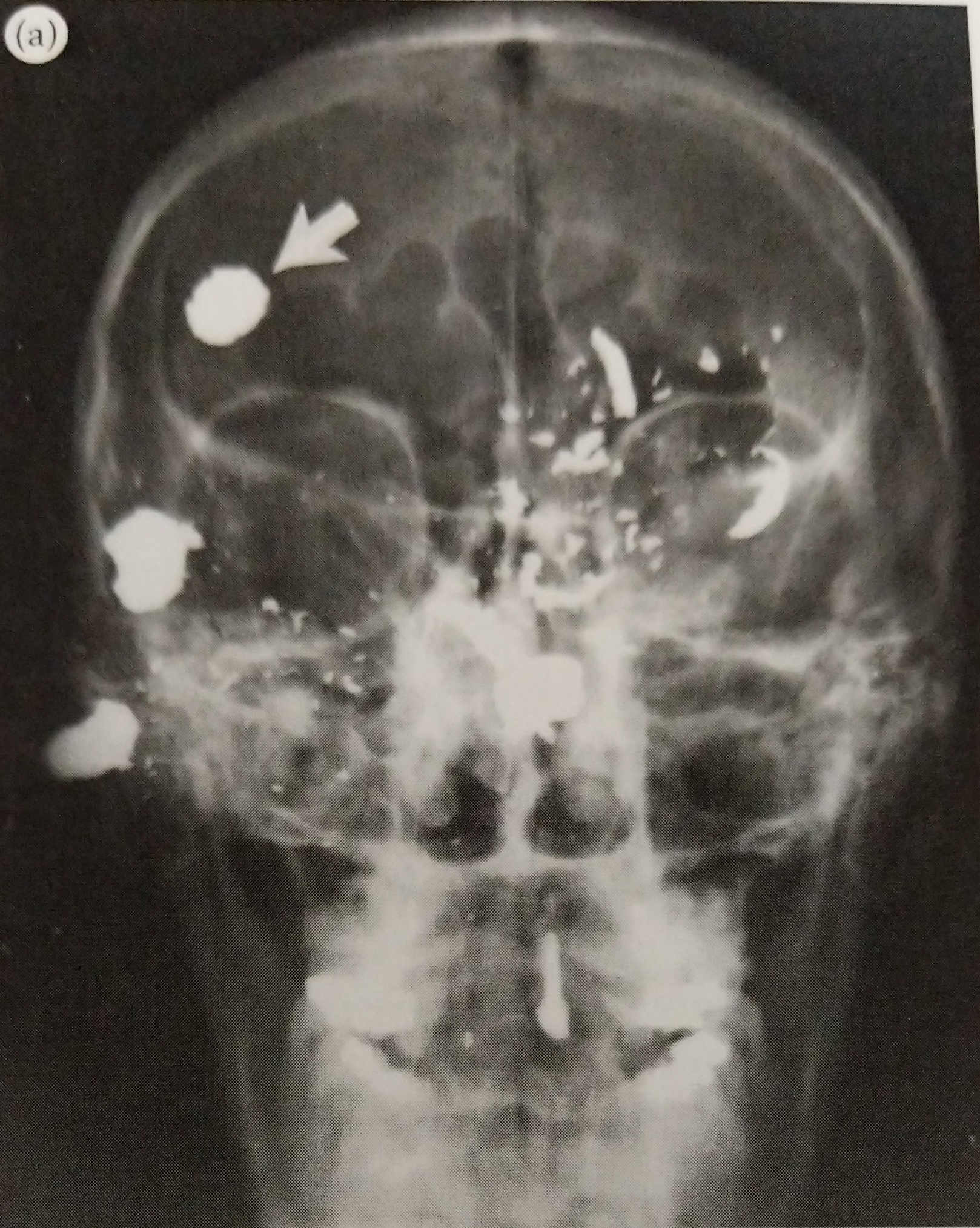

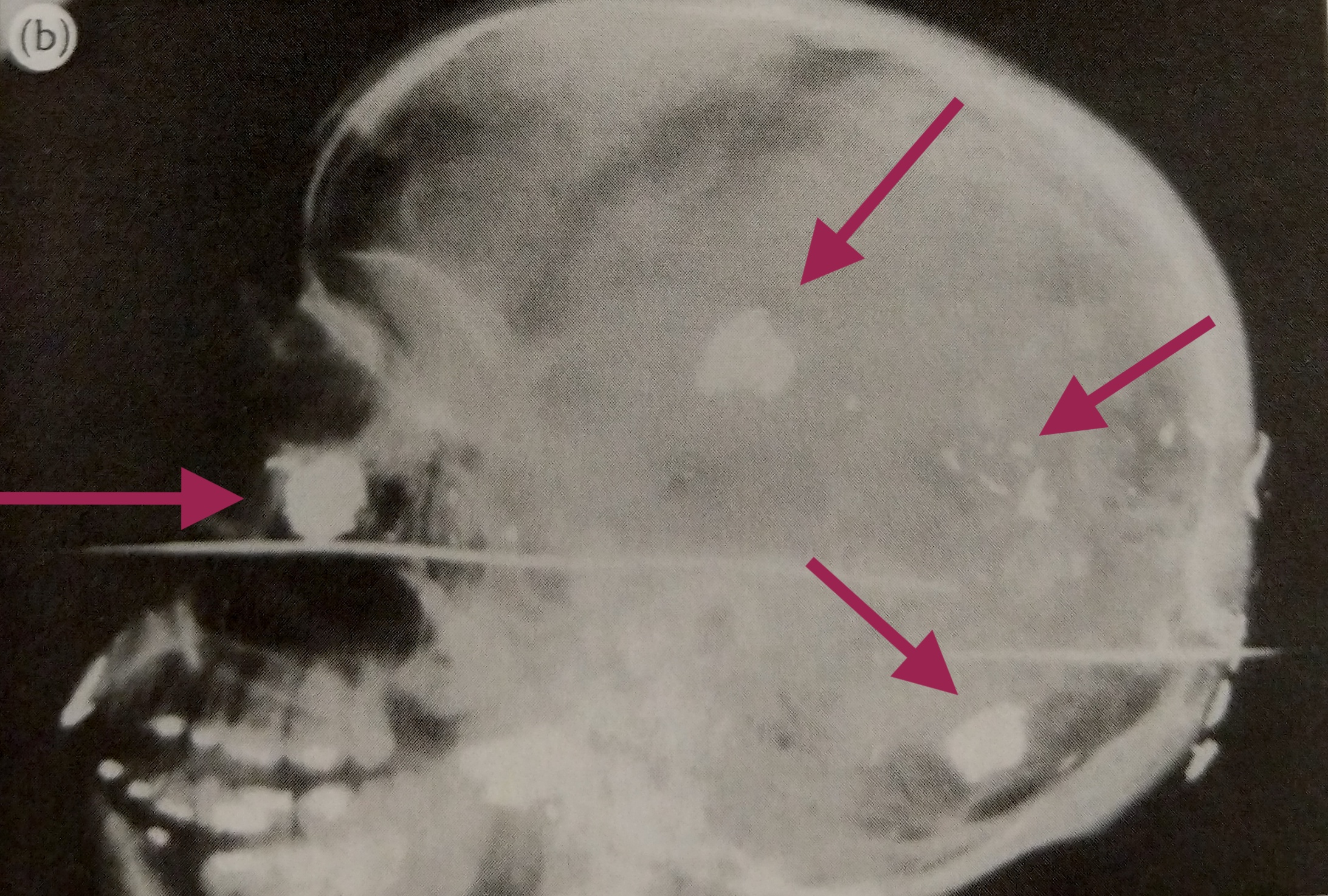

Bones are constantly being broken down and rebuilt. So as long as there was a regular influx of radium, Byers’ bones used it to make even the most basic of repairs to his skeletal system. I read that his teeth had such a high radiation output that they’d light up a photographic plate on their own—no x-ray machine needed! By 1931, he had consumed 1,400 bottles of Radithor, accumulating roughly three times what’s now considered to be the lethal dose.

Here’s where it gets bad for the 50-something-year-old. It started with aches and pains, and soon his athletic build deteriorated and he dropped down to 92 lbs. His bones were splintering and dissolving. Byers not only suffered from blinding headaches, but he lost most of his teeth as well as most of his entire jaw. Oh, and then there were the holes that formed in his skull from his bones literally disintegrating. Byers died in March 1932, only five years after he started drinking Radithor.

The End?

Despite the trauma endured by Byers, Bailey pushed back, stating that he had drank more Radithor than anyone and never suffered an ill effect. Fortunately the FTC shut him down soon after Byers’ death. But did that stop our ingenue? Yes and no.

Bailey went on to create a radioactive paperweight, “Bioray,” which acted as a miniature sun for people unable to work outdoors. He also sold the “Adrenoray,” a radioactive belt clip and the “Thoronator,” a refillable “health spring” for the home or office that infused tap water with radon gas. Fortunately, none of these newer products proved to be very radioactive.

So there you have it! That’s the story of Radithor. If you’d like to read more about this, and other radiation disasters, I recommend reading “Atomic Accidents“. I’m currently working my way through it; it’s very interesting. I’m not sure why I find this particular story so fascinating though. I’d like to cover other crazy ways we used radioactive products (butter, chocolate, condoms, etc.) so hopefully I’ll get to those in a future post! Thanks for reading.