When a homicide case comes in, particularly a gunshot, I cringe. Most likely not for the reason you’re thinking. My reaction has less to do with the loss of life and more to do with the fact that if the bullet didn’t exit the body, there’s a good chance this case will come back to me. Cold, I know, but the morgue hardens you.

While it’s something I’m researching, I still don’t understand ballistics enough to go into the physics behind guns. What I can say is that whether the bullet exits a body has a lot to do with the bullet itself and where on the body the victim was shot.

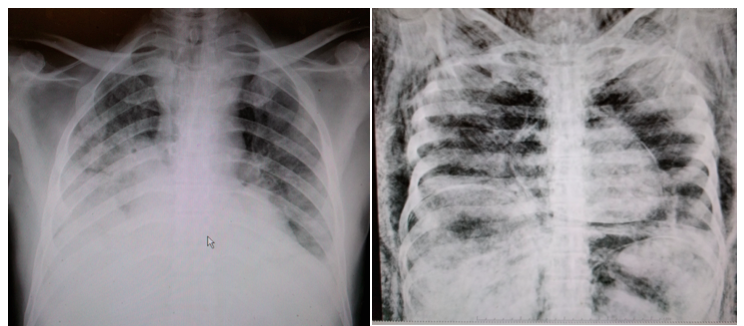

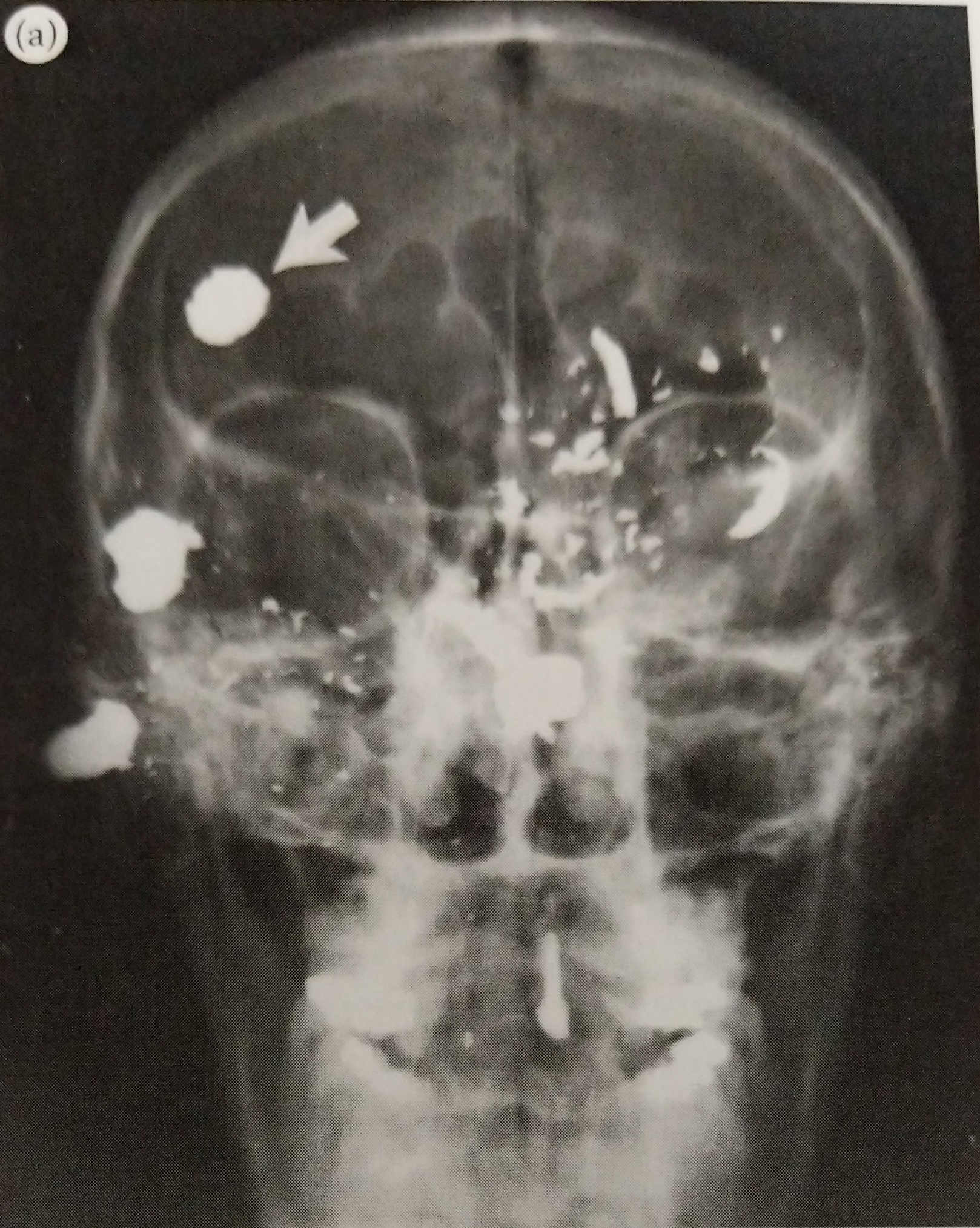

I’m learning that bullet identification and recovery are important for several reasons. One, knowing the specific location of a bullet saves the pathologist a lot of time and minimizes needless searching during the autopsy.

Two, it’s important to carefully count the number of bullets present. They have to be correlated with the entrance and exit wounds, otherwise a discrepancy can lead to a search at the crime scene. It is possible that multiple bullets can enter through a single entrance wound, but typically only when automatic weapons are used.

Lastly, x-rays can reveal information about the angle and direction of fire. Small metallic fragments produced when a bullet strikes bone may lead directly to the bullet and clearly indicate the bullet’s path. This helps investigators recreate the positioning of the victim and their assailant.

**********************

And since it’s never safe to assume that there’s an exit wound, x-rays are mandatory.

The first thing I do is visually examine the body. I check the head, chest, arms, abdomen, and legs for any bullet holes. My partner does the same. Two sets of eyes are better than one. If we find any, then I make mental notes of areas that need to be more closely examined for bullets on the x-ray.

Then we scan the whole body using x-rays. Even if it seems that the victim had only been shot in the head, the bullet could have traveled into the neck or chest. Bullets frequently end up in a site that’s far away from their entrance points, especially if they’ve hit a bone, so it’s important to be thorough.

If the full body scan shows that there are bullets, I will often walk over to the body and try to feel for the them. Sometimes the bullet is superficial, meaning it’s just below the surface of the skin. They’re easily felt and sometimes they can even be seen as small bumps. If that’s the case, I put a piece of tape over the bullet and mark it with a “x”. The pathologists appreciate it because it makes for a very easy retrieval.

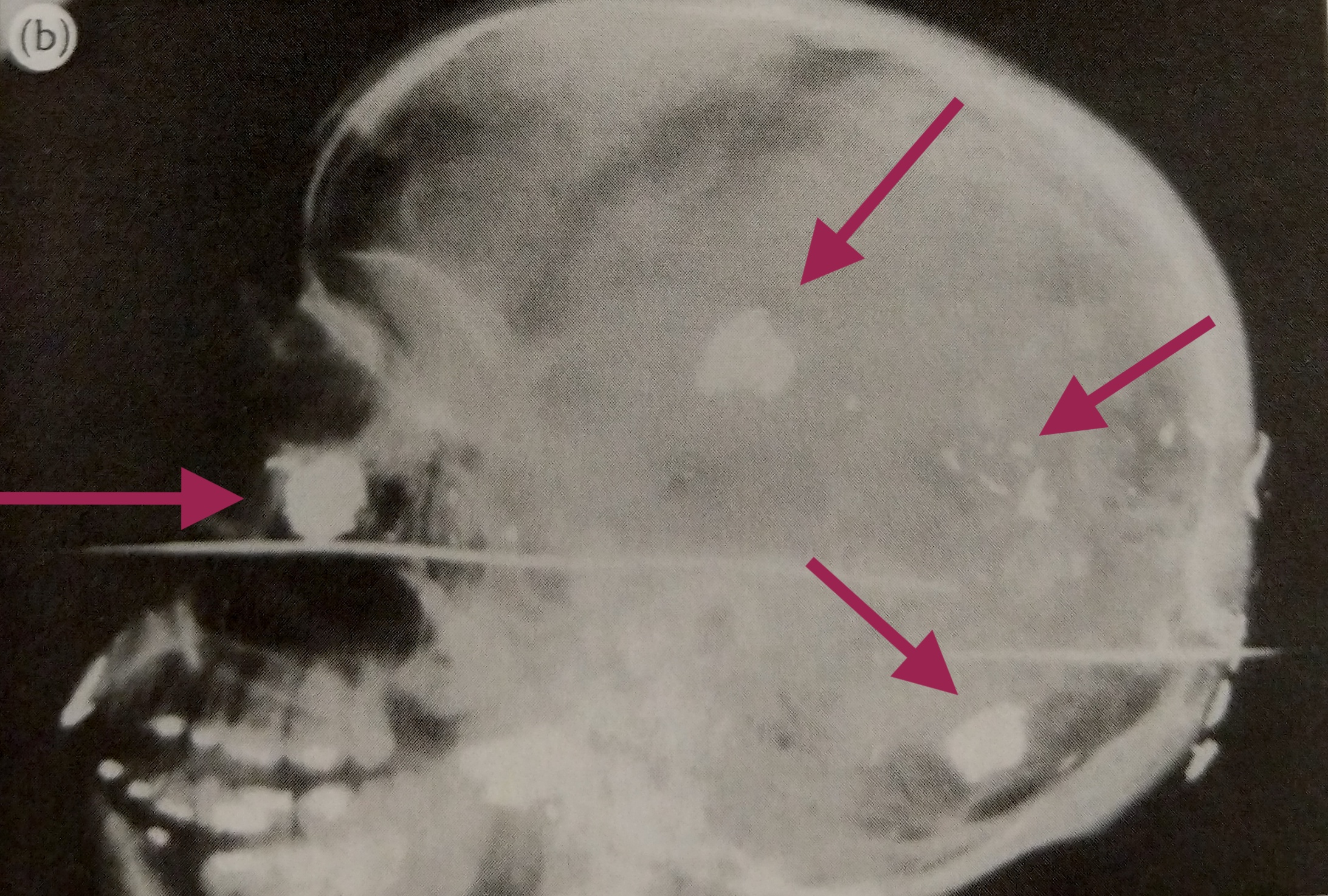

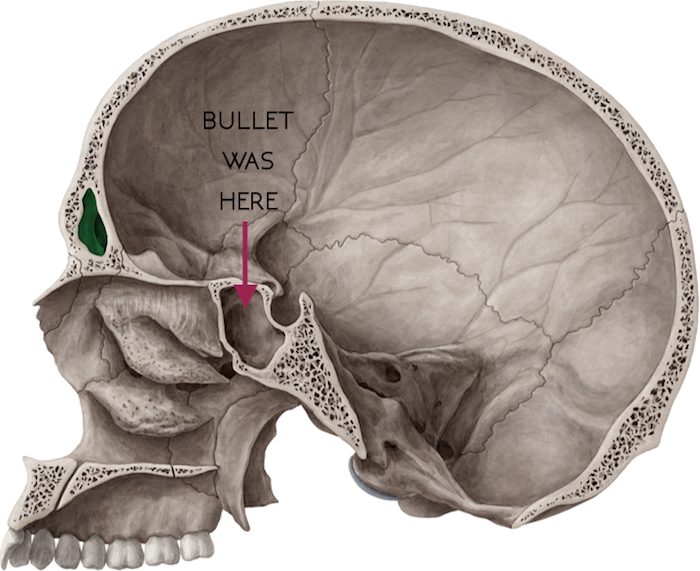

If the bullet isn’t easily palpable and is located within the skull, neck, chest, abdomen, or pelvis, then additional image needs to be taken. Specifically, a lateral view. Instead of x-rays going from the front side of the body to the back like in the AP view, the lateral lets you see left to right. It gives me and the pathologists an idea of whether the bullet is more anterior (toward the front of the body) or posterior (toward the back).

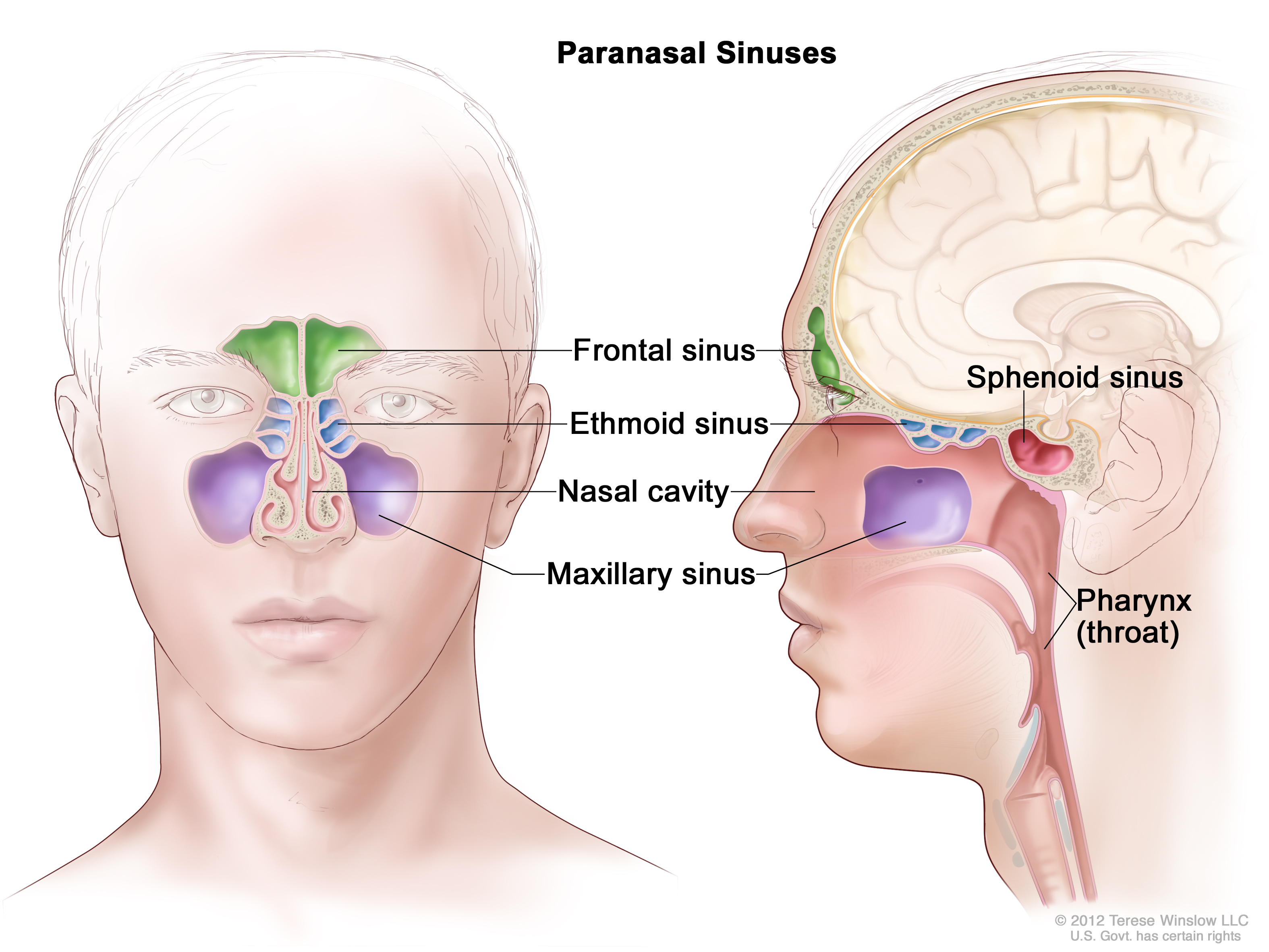

After I submit my x-rays and return the body to the cooler, I’m done with that case and it can now be autopsied. But despite my best efforts, bullets can be difficult to find. It could have shifted during the autopsy. I’ve seen bullets that appear to be in one area only to wind up in a lung that has already been removed from the body. I’ve also seen bullets, particularly those in the skull, get lodged within the sinuses. In the event of the latter, chances of the body being returned to x-ray are high.

I don’t like when bodies come back. By this point, the autopsy is underway and the chest cavity is open. Most if not all of the organs removed. The skull cap will also have been sawed off, skin peeled down over the facial bones, and brain removed. It’s a much different version of the body than I had previously worked with.

**********************

Recently I worked on a case where a man had been shot in the head. A large bullet fragment was lodged somewhere inside of the skull. The pathologist and tech tried to access it, but without x-ray, they were working blind. At this point, the body is returned to radiology and we use fluoroscopy to image the body.

Fluoroscopy is x-ray in real-time. When I take a regular x-ray, I’m given a static image in return. But with fluoroscopy, I can see a moving image. For example, if I were to stick my hand into the empty skull cavity, I could see my fingers wiggle in real-time.

When using fluoroscopy, forensic x-ray techs will often use a scalpel or tool with a long handle to help locate bullets. This keeps our hands out of the x-ray beam, minimizing our dose. I was using such a tool during this case, but our equipment wasn’t working very well. The image on the screen was very poor quality and I had a difficult time recognizing where I was within the skull.

The pathologist and her tech were anxiously awaiting my verdict, standing safely behind a lead-lined barrier. My partner, a new tech who had only recently joined the team at the morgue, was operating the C-Arm for me while I searched. I was starting to feel the pressure, so I decided to rely on my instincts. In order to do that, I had to ditch the tool and use my hand. This isn’t something you should do, as it increases your radiation exposure. However, I needed to feel the structures and I needed to find the bullet fast.

I saw my hand moving on the screen in front of me, inching closer to the dark spot: the bullet. I was hyper focused until I wasn’t. Something has pulled me out of the blissfully ignorant bubble I had put myself in. Suddenly I was very aware that my fingers were pushing along the ridges of facial bones and squeezing into holes that were inside of a human skull.

What the f*ck am I doing?

I had seen the other more seasoned x-ray techs do this dozens of time, but this was my first time as lead tech. There was no one else to ask. My new partner had just started and, to her, I was the seasoned tech.

“Is it stuck inside of the bone?”

I heard the doctor ask me a question, but clearly I had my hand inside of a man’s skull and couldn’t form a coherent response.

Sorry, I’m a bit busy not thinking about where my hand is right now. Okay, just focus on the screen. Feel the bones, identify the landmarks, find the bullet. Easy peasy.

After more palpating and a lot of internal shrieking, I felt it. I found the bullet. It was wedged within the sphenoid sinus. I grabbed my tool, used it to replace my finger, and called the pathologist over for removal.

I felt victorious, upset, super gross, and exhausted all at once. Thankfully it was near the end of my shift so a hot shower wasn’t too far off.

It’s a weird thing, being an x-ray tech in a morgue. On one hand, x-ray techs have clearly defined responsibilities. We’re taught to work within our scope of practice—provide exceptional patient care, minimize exposure to patients and personnel, evaluate images and ensure they’re of diagnostic quality. That’s the succinct version anyway. However, I’m learning that the lines which define our scope are blurred here. One day you’re taking a routine chest x-ray and the next you’re wrist deep inside of a dissected skull.