“A donated organ can save a life, but a body provides the foundation to save many more.”

In 2009, my mom and I went to see Body Worlds, a traveling exhibit of dissected human bodies preserved through plastination. I had seen it before, but it’s always better to experience these things with another person. I wanted her to see why I was in such awe of the human body. I left the museum that day having made three decisions: my mom is a good sport, $30 for a organ donor t-shirt was totally worth it, and I am donating my body.

Up until that day, I hadn’t given much thought to what would happen to my body after I died. Do I want to be buried? Cremated? Shot into space? To be honest, none of that crossed my mind. I was 25 and invincible. But after walking through the Body Worlds exhibit for the second time, I knew that a coffin six feet under ground wasn’t for me. My atoms crave fame. (Not really. They crave caffeine.)

Before leaving the exhibit, I used one of the computers there to sign up as a donator. Instead of donating my money, however, I opted to donate my body. It was almost too easy, and part of me believed that I had just sent one of those “wish you were here” museum postcards to a family member. But weeks later I received confirmation in the mail—I even got a fancy ID card to carry with me so people know what to do with my body when I die.

Side note: To be fair, it wasn’t just Body Worlds that had led me down this path. By this point in my life, I had attended several cadaver labs and read “Stiff” by Mary Roach. This book opened my eyes to not only the need for cadavers, but the very important purpose they serve in a number of research capacities. It’s a fascinating book, and she’s a brilliant author. I recommend reading it.

Nearly 10 years later, I haven’t changed my mind. My body will be donated when I die. What has changed is who I am donating it to. While the Body Worlds exhibit is enlightening, there isn’t much need for bodies to be plastinated and put on display. While it serves an educational purpose, it’s self-serving. What is needed, however, are bodies for medical students, anthropologists, ballistics experts, and first-responders.

In 2016, National Geographic reported that the demand for cadavers is up, but the supply is down. The Anatomical Gift Association of Illinois reported that annual donations fell from 760 in 1984 to 520 in 2015. This was disheartening to read because body donation is such a wonderful gift. There are more than 20,000 enrolled first-year medical students, and for them, anatomy class is a rite of passage. With about six students assigned to one body, it really limits the amount of hands-on learning future doctors have.

According to NatGeo, in 2008, Colorado and Wyoming were 20 bodies short of the 158 cadavers requested by the states’ medical schools. And with physician assistant and nurse practitioner programs now utilizing cadavers, in addition to vocations outside of medical school, the supply is even more strained.

“There are more than 120 million registered organ donors in the United States, and an average of 79 people receive transplants each day, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The federal government does not monitor whole body donations in the United States, but researchers estimate each year fewer than 20,000 Americans donate their bodies to medical research and training.”

This doesn’t sit right with me. I have gained so much knowledge from the generosity of body donors, and I’m not even in medical school. I don’t know what happens when we die, but I can’t imagine that I’d rest easily knowing that I opted to keep my body in a box instead of helping future medical professionals better understand anatomy, physiology, and pathology.

Now I’m not here to tell you what to do with your body. It’s yours. But I do hope that maybe I can answer some questions for you in the event that you’re considering body donation.

What is body donation?

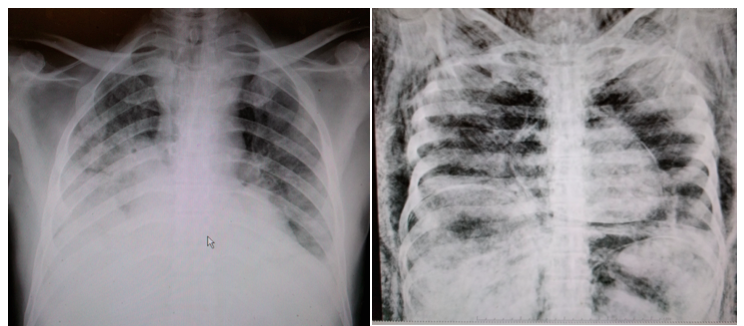

Simply put, body donation is the donation of a whole body after death for education and research. Donated bodies are primarily used for medical education and research, but cadavers have helped industries outside of medicine, including NASA and car manufacturers.

What will happen to my body?

That all depends on where you donate your body. In medical settings, donated bodies are mostly used for gross anatomy and surgical anatomy. In 2015, Vice published an in-depth article about what happens to your body after it’s been donated. I recommend checking it out. But to be blunt, you will be dissected. Remember that fetal pig in high school biology? More than likely, though, you’ll be treated with much more respect than that pig.

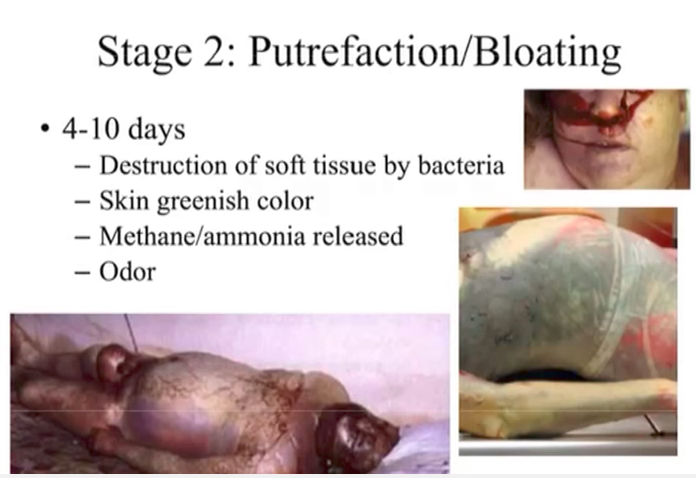

Your body will be embalmed, which means your blood and other bodily fluids are replaced with chemical preservers. This makes it so your body will last instead of decompose. Side note: read my previous post all about decomposition.

In my personal experience with cadavers, I’ve worked with whole bodies and well as parts, such as arms and legs. I have seen skulls cut open to reveal the hollow space where the brain once sat. I have also seen heads split in half down the middle to reveal the inner workings of the nasal and pharyngeal areas. I have been the person doing the dissecting, and I’ve also been the person who observes the body post-dissection. It all depends on the class you’re taking and career path you’re heading down.

If you’re looking for a moving first-hand account of a cadaver lab, I recommend reading “Body of Work” by Christine Montross.

How can I donate my body?

There are several ways to do it. First and foremost, you can opt to be an organ donor. This is much more common than whole body donation. Working at the morgue, I receive a lot of Gift of Hope patients. These are bodies that have already had their corneas, organs, long bones, and even some skin removed.

My next recommendation is to check with your state to see if they have a formal organization. Illinois, where I am located, has the Anatomical Gift Association. It receives, prepares, preservers, and distributes donated human remains to medical education and research institutions across Illinois.

You might also consider research facilities like a “body farm”. The most notable one, at least in my opinion, is located at the University of Tennessee. It was founded in 1981 and has been used to study human decomposition. Similar projects have followed at Western Carolina University, Texas State University, Sam Houston State University, Southern Illinois University, and Colorado Mesa University. All six are, or at least at one point, accepted human donations. If you like podcasts, here’s a great one about body farms from the guys at Stuff You Should Know.

What happens to my body when they’re done?

That’s a great question. In my research, I’ve read that most places hold a type of memorial service or ceremony. Certain institutions will invite family members, while others prefer to limit it to the students and faculty that worked with the cadavers. It’s a great way to show respect and gratitude for the generous gift. Bodies are then cremated, and their remains are returned to their families.

So there you have it. It’s a very quick overview of body donation. If you are considering it, I encourage you to research further. Like me, you might change your mind about where you’d like your body to go or what you’d like it used for. It’s an important decision, and one that shouldn’t be made impulsively. That said, it’s truly a wonderful gift and one that I am extremely proud to give.